Found in Translation?

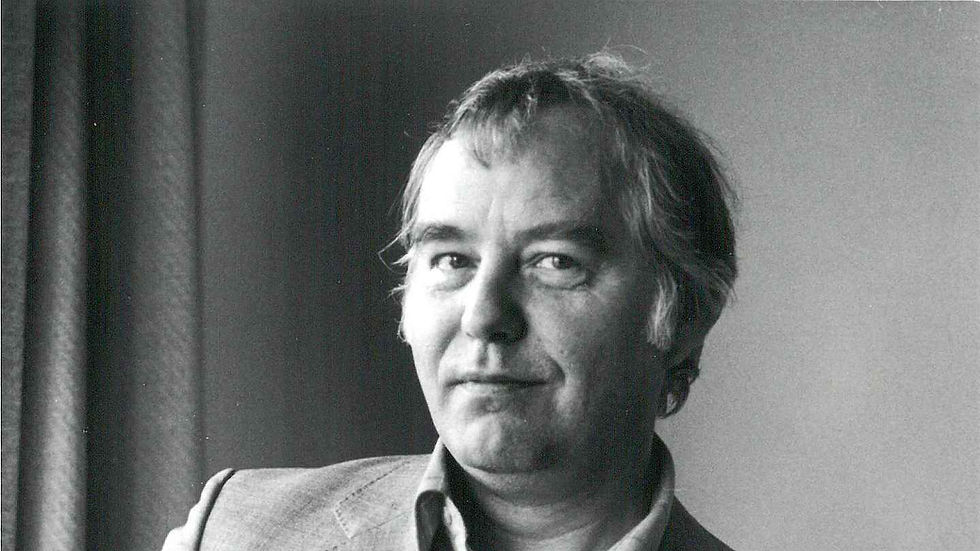

- Árni Heimir

- Apr 17, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 7, 2023

Last week, I was invited to talk about my research at a US university, where my book, Jón Leifs and the Musical Invention of Iceland, had been required reading for a course earlier this semester. It was a real pleasure meeting the students (albeit only via Zoom) and discussing my work, and it made me realize how rarely I verbalize the process of doing research and writing about music. I suppose this is true for most academic writers, but it’s a shame, because it is such an interesting topic!

Of course, scholars will always be guided by their material and their argument, but there is still considerable freedom in how we construct our writing, how we present our evidence, on both macro and micro levels. Each writer will also have a different relationship to the act of writing vs. revising, which I find absolutely fascinating. For example, I tend to do the hard, laborious work at the back end of the writing process; that is, I prefer to write quickly, to capture the flow of my thoughts on the page, and then I will happily spend weeks and months revising, adding, cutting, restructuring the prose on every level. To me, this isn’t laborious work at all. I thoroughly enjoy being my own editor and seeing my writing gradually transformed into something half-decent (I hope) by the work I put into it. Other writers may prefer to do the hard work at the front end, painstakingly crafting their sentences in their minds before typing them on the computer or writing them down on paper. In the end, it’s probably the same amount of work either way.

There is also the question of language, which we discussed in detail in last week’s seminar. I write in two languages, Icelandic and English, but I do most of my academic writing in Icelandic, my native tongue. Some of my articles and books are only available in this language, but sometimes I have translated my own work into English. Thus, there are two different versions of one of my books, and several of my articles—one in Icelandic, which will invariably bear the earlier publication date, and another in English.

This is never just a straightforward translation project. Each language has its own conventions, also within the academic discourse. Each book or article will have a presumed audience and these are rarely identical for publications in two considerably different linguistic regions. English is, of course, the lingua franca of current international scholarship and writing in that language requires engaging in a dialogue with academic colleagues on a given subject. Iceland, on the other hand, has very few musicologists, and thus my writing in Icelandic is aimed for a broader audience: usually what one might call a well-educated layperson, or sometimes an academic community that does not specialize in music. On the other hand, Icelandic is an often complex, stylized language in a way that English is not; Icelandic academics are expected to write with linguistic flair and command of style that generally goes beyond what one expects of scholars writing in English, where clarity and conciseness are valued.

Thus, the material will always need to be adapted/adjusted to a different audience, as well as different academic conventions. While my book, Jón Leifs and the Musical Invention of Iceland, was published in 2019, it’s based on my earlier biography of the composer, published in Icelandic a decade earlier. Reshaping the book for a foreign readership was a long and arduous process. I had to substantially expand, and often fully rewrite, my treatment of local history, literature, and nature, while I would cut entire paragraphs when I found them to be relevant only to a local readership. This was particularly true of Chapter 1, where, in the earlier version, I discuss the composer’s forefathers in a detailed manner that I suspect foreign readers would find unbelievably tedious.

On the other hand, a musically literate reader will appreciate—or even demand—a detailed discussion of the music itself. For the English version of my book, I rewrote virtually every single discussion of Jón Leifs’s music, in order to make it more substantial and meaningful to readers who were likely to understand even basic terms such as “fully-diminished seventh chord.” It is telling that the English volume contains dozens of notated music examples; the Icelandic version doesn’t have a single one. Overall, I would say that less than 50% of Jón Leifs and the Musical Invention of Iceland is translation; well over half of it is some combination of new or newly-written material and passages that are, to a greater or lesser extent, adapted for a new audience.

The two “versions” of my book on Jón Leifs were published ten years apart, so I had lived with the earlier iteration for a while before even attempting the “translation.” My current book project feels very different, as I am working on the Icelandic and English versions concurrently. Again, I find the English version to be more demanding in a strict academic way, the Icelandic one in terms of style and structure. Yet this project feels in some ways less difficult than the earlier one, primarily because the historical background to the book’s subject—exiled musicians from Nazi Germany and Austria—is universally understood. Yet I find myself employing essentially the same method as before. First I attempt a “rough” translation, and, once this is complete, I give myself complete freedom to treat the English version as its own independent work. This allows me to constantly adjust both the tone and the content of each volume independently. While it certainly requires a lot more effort, I hope it will also lead to a more convincing outcome.

Comments