“Quite Good, for a Housewife”?

- Árni Heimir

- Jun 30, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 1, 2023

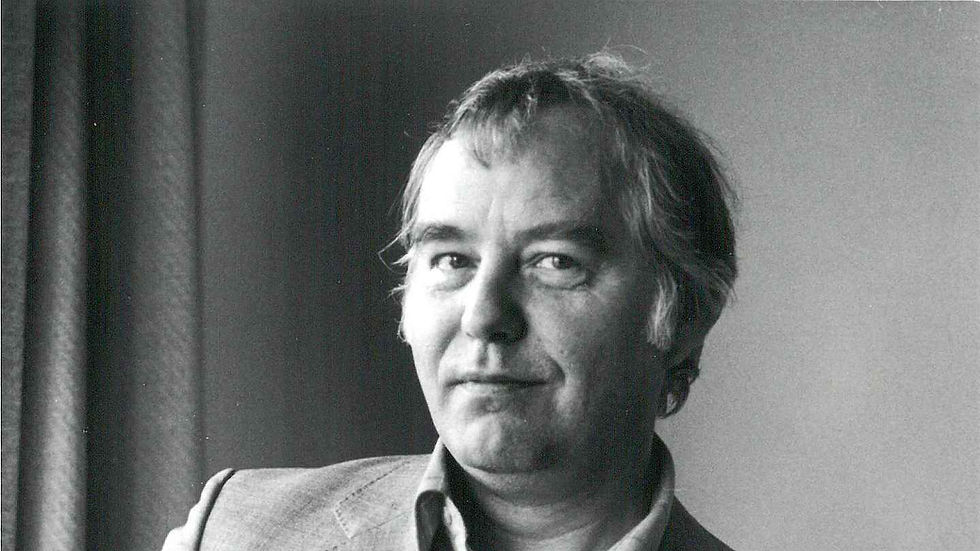

As my book on the exiled musicians who settled in Iceland in the 1930s is nearing completion, I am also finishing up another long-term project: a biography of the Icelandic composer Jórunn Viðar (1918–2017). She was a remarkable figure in many ways. Not only was she Iceland’s first woman composer, but she was also an excellent pianist, and a wonderful human being with a brilliant sense of humor. I was fortunate enough to get to know her in the early 2000s, when I played the piano part in one of her choral works (you can listen here), and I even recorded one of our conversations in 2003—something for which I am now incredibly grateful.

Following her initial music studies in Reykjavík, Jórunn Viðar studied piano with Kurt Börner in Berlin in 1937–1939. While she had composed a few piano pieces as a child, it was during this time that she began taking composition seriously. At a violin recital at the Hochschule für Musik, she heard a female student perform an encore of her own creation, “and then I thought, why shouldn’t I be able to do something like that, too?” Jórunn had to return to Iceland in a hurry in summer 1939 as war on the continent seemed imminent, and it was in Reykjavík that she took her first formal composition lessons—with Victor Urbancic, an exiled Austrian musician who, coincidentally, is among the main subjects of my other book project. She then continued her studies in New York in 1943–1945, taking composition lessons with Vittorio Giannini at Juilliard and private lessons with the Polish pianist Helena Morsztyn, whose grandmother had, remarkably, studied with Chopin.

Jórunn Viðar had a remarkable commitment to music and refused to be intimidated by gender stereotypes. She had a successful career as a composer, writing dozens of songs and several works of solo and chamber music. In terms of orchestral works, however, she was mostly active in the early 1950s, when she wrote two ballet scores, Fire and Ólafur liljurós (both recently issued by Chandos) as well as the first full-length score to an Icelandic film, The Last Farm in the Valley (Síðasti bærinn í dalnum). It seems that she didn’t, in the long run, get the large-scale opportunities as a composer that she certainly deserved. Her only commission from the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, the piano concerto Slátta, came only decades later, in 1977.

Jórunn Viðar was the first female pianist in Iceland to give large-scale solo recitals on a regular basis, performing works by composers such as Chopin and Schumann, as well as local premieres of works by Bartók, Stravinsky, and Shostakovich, composers whose works were rarely heard in live performances in Iceland in the 1950s. While it is difficult to point to specific cases of discrimination in the reception of her own compositions, it is quite clear from reviews of her piano recitals that she was judged using language different from that used to describe the playing of her male colleagues.

In their reviews of Jórunn Viðar’s playing, Icelandic critics—all of whom were male—repeatedly refer to her “femininity” in two distinct ways. The first is through her physique: if they find her playing too weak, it is because she is a woman, yet when she plays forcefully, they are surprised that a woman can play in such a way. At her debut concert in 1947, one critic noted that she drew more power from the instrument “than might be expected from such a slender musical lily.(!)” In 1954, Björn Franzson, one of Iceland’s leading music critics at the time, was amazed that she was able to play Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 3 with such power, noting that “in this masculine work, one almost didn’t notice that the soloist was a woman.”

The other idée fixe of Icelandic critics was that it must be impossible for a woman to devote herself to the piano in the same way that a man could, since she was bound to be too busy with housework and raising her young children. In fact, Jórunn Viðar had a housekeeper/nanny for decades, which allowed her to devote herself fully to music, yet critics constantly referred to the “difficult circumstances” that would undoubtedly allow her to “only occasionally” focus on the piano. Nowhere was this view more clearly stated than in Franzson’s review of her solo recital in 1954, which included Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, Chopin’s Scherzo in B minor, and Schumann’s Kreisleriana: “When beautiful music is presented in such an attractive and pleasant way, one cannot help but think: Let other housewives do a better job.” The tone of the Icelandic phrase (“Geri nú aðrar húsfreyjur betur”) is difficult to capture fully in translation, but in any case, the misogynistic tone is perfectly clear.

Needless to say, this review infuriated Jórunn Viðar more than any other she received. More than 30 years later, she recalled it in a newspaper interview: “It was as if I had come running straight from the washtub with discolored nails on each finger, and that it was a miracle that such a human being could play the piano at all. I was so angry!” The critic soon heard of her displeasure, and, according to Jórunn, was astonished: “But I meant it as a compliment!,” he supposedly said.

In the end, it seems that such misogynistic views among Iceland’s leading critics and cultural moguls deflated Jórunn Viðar’s ambition as a pianist. While she gave five solo recitals in Reykjavík between 1947 and 1955, as well as appearing several times with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra in concertos by Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, and Chopin, she was never able to fully convince her male critics of her worth. She gave her last large-scale solo recital in 1955, after which she took on a role that the male-dominated music world had already carved out for women: as a composer of songs and vocal accompanist. Thankfully, several recordings exist of Jórunn Viðar as a solo performer; they would certainly make a worthy release.

Comments