The Ones Who Were Rejected

- Árni Heimir

- Aug 1, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 25, 2023

As I write the concluding chapter of my book on the exiled musicians who made it to Iceland from Germany in the 1930s, I find it appropriate that I should be doing so in Berlin, which is where the whole idea for the book was born—exactly four years ago, in August 2019. I had decided to spend a month in Berlin, where I borrowed a friend’s apartment and took an advanced German course at the Goethe Institute. Berlin always has a peculiar effect on me; its history is more palpable, more stirring, than in any other city I know. Thus, it was probably inevitable that I should recall the story of Robert Abraham, the Berlin music student who was forced to leave the city in 1934 and arrived in Iceland a year later, by way of Paris and Copenhagen. Although I had written on his life and work before, I realized then that there was much more research to be done, archives and private collections to be examined, colleagues, students, and family members to be interviewed. The same also had to be done for the other musicians who took the similarly unexpected route to Iceland as the Nazis made life in their homeland increasingly unbearable.

This has without a doubt been the most intense and heartfelt project I have ever undertaken as a musicologist. Most of my previous research has been on music in medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, and on Icelandic composers and music life in the twentieth century. While these have certainly served a good purpose, nothing I have ever done has felt as relevant as writing this, precisely as the world is faced with a refugee crisis on a scale not seen since World War II. Also, having the opportunity to get to know the families of these musicians, who have entrusted me with their stories and all the materials I could hope for to tell them properly, has been a tremendous honor.

While I knew that my book would focus on the three musicians who were, through little more than sheer luck, allowed to reside in Iceland in the 1930s and made a huge impact on the local music scene, I was more surprised that a substantial part of my research would focus on those who were not allowed in. Their stories have never before been told, and their names are still unknown in Iceland. This is largely because the documentation is both scarce and scattered. A few rejected applications from musicians survive in the National Archives of Iceland; other attempts never got as far as a formal application, but evidence for them can be found elsewhere.

Confronting the xenophobia and cultural chauvinism that was a part of Icelandic culture in the 1930s and beyond has not been an easy task. The government, led by Hermann Jónasson, who became both Prime Minister and Justice Minister in 1934, ran a hardline policy against all immigrants, but especially Jews. While their exclusion was never official government policy, by the second half of the 1930s it was clear that only in rare cases would they be granted permission to reside in Iceland. For example, in 1937, Jónasson insisted, in a conversation with the chargé d’affaires of the local Danish Embassy, that “Iceland has always been a pure, Nordic country, free of Jews, and those who have made it in in the last few years shall be sent back out.” Jónasson had the habit of signing all applications for asylum himself, usually with a negative “Nei (No), HJ.”

All in all, five musicians of Jewish descent are known to have applied for or enquired into the possibility of emigrating to Iceland in 1937–39, but to no avail. One of them made it to Iceland but was deported, two were denied residence permits, one found another destination while in the process of applying, while the fifth only made an informal enquiry and was later murdered in a Nazi extermination camp.

The only one of these to reach Iceland at all was Fritz Dehnow (1889–1960). He was an attorney by profession but also loved music; he played piano and violin and was also a talented arranger. He fled Germany in 1936 for São Paolo, Brazil, but a year later he arrived in Iceland, hoping to win back his ex-wife, Ilse, who had settled there in the meantime. In this he had no success; she married an Icelander and remained there until her death in 2004. Dehnow resided in Reykjavík in autumn 1937, advertising in newspapers for students in piano, violin, and music theory. He was deported a few months later, but made it to Argentina and worked as a musician in Buenos Aires.

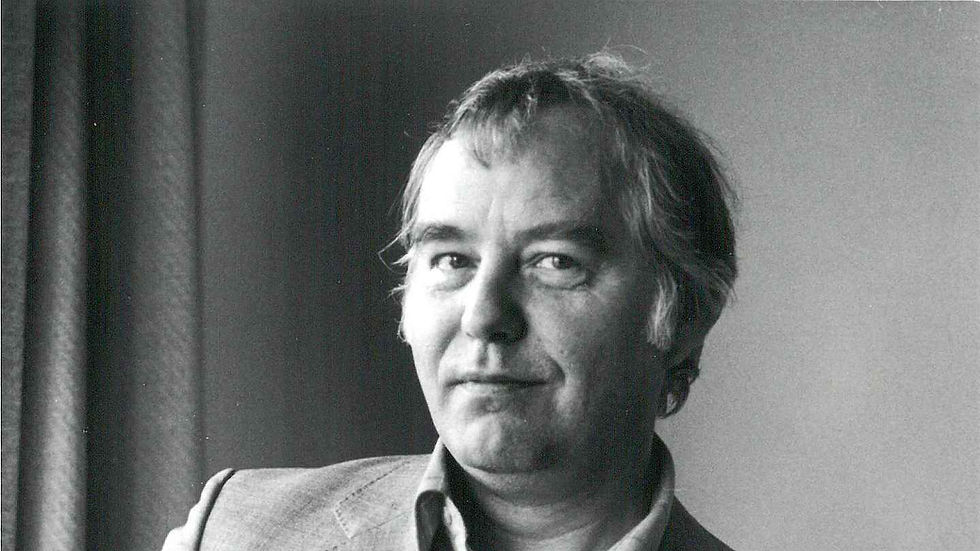

Two other Jewish musicians whose applications were rejected were Paul Erdensohn (1889–1956) and Ludwig Misch (1887–1967). Erdensohn was a violinist and composer from Dortmund, who had studied at the Berlin Academy of Music with such luminaries as Joseph Joachim and Henri Marteau. He was considered an excellent string pedagogue and composed several books of etudes for aspiring violinists. In December 1938 he applied for a residence permit in Iceland along with his wife and brother Caesar, a lawyer, but they were all rejected soon afterwards. Instead, they sailed to China, still an open country with no visa requirements and therefore a popular destination, although the conditions there were nothing short of terrible. Misch (seen above) was a well-known Berlin musician; until 1933 he was on the faculty of the distinguished Stern Conservatory, was a music critic for the local Berliner Lokalanzeiger, and wrote program notes for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. He applied to the Icelandic Ministry of Justice in January 1939 but was rejected soon afterwards, despite a glowing letter of recommendation from Wilhelm Furtwängler, who asserted that Misch, widely known in Berlin for his “outstanding talent,” would be an asset to any musical organization. Amazingly, Misch managed to survive the entirety of the war in Berlin, and moved to New York in 1947, where he worked as a musicologist.

Another musician who considered emigrating to Iceland was pianist and sociologist Alphons Silbermann (1909–2000). Once the Nazis took power, he emigrated to Paris, where he worked as a bar pianist and served tables at restaurants. In his autobiography, Silbermann recalls standing in line alternately at the Australian and Icelandic consulates (presumably the Danish consulate in Paris, since Denmark still managed Iceland’s foreign affairs), in the hope of getting to whichever place was first to accept him. Not surprisingly, given Iceland’s strict immigration policy, his Australian papers came through first. Silbermann arrived in Sidney in autumn 1938 and began a career as a musicologist, teaching at the Sidney Conservatory of Music.

The most famous of this group of musicians was the only one to be murdered by the Nazis. The outstanding composer and pianist Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944) had studied with Arnold Schoenberg in Vienna before settling in Prague. As Nazi troops marched into the city in spring 1939, Ullmann pursued every possible means to get out. In June that year, he wrote a letter to Victor Urbancic, an Austrian musician who had recently emigrated to Reykjavík, asking if he saw any possibility for him to obtain work in Iceland. Ullmann’s letter is brief, only a few lines on a single page, yet his despair is obvious; he asks Urbancic if there might be any possibility for him to find work as a pianist in one of Reykjavík’s cafés, since he would gladly take such work in order to escape the Nazi regime. Urbancic’s reply has not survived but he presumably gave a realistic assessment, that by 1939 it was completely impossible for a Jewish refugee to obtain residence and work permits in Iceland. Three years after Ullmann wrote his letter, he was arrested and transported to the Terezín (Theresienstadt) prison camp in northern Bohemia. Despite the deplorable circumstances, he showed remarkable perseverance, composing and organizing musical performances, including the one-act opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis. In October 1944, Ullmann was deported to Auschwitz and murdered there along with his wife.

It is tempting to wonder what the contributions of these talented musicians might have been, had they been given refuge in Iceland during the Nazi reign. Would there have been more choirs, more talented young violinists, a more decisive cultivation of musicology in Iceland? Might we have dozens of additional works by Viktor Ullmann, perhaps inspired by Icelandic vernacular music, or the mountains, geysers, and volcanos of his new homeland? Given the xenophobia and antagonism of both leading politicians and the local musicians’ union, Iceland was unlikely to have accepted more exiled musicians than it did. This was, of course, Iceland’s loss, but perhaps it also serves as an important reminder, in our own fiercely divided, war-ravaged times, of the possibilities that can come out of seemingly impossible situations, when decency and humanity are allowed to lead the way.

Comments