Discovering Iceland’s First (Unfinished) Opera

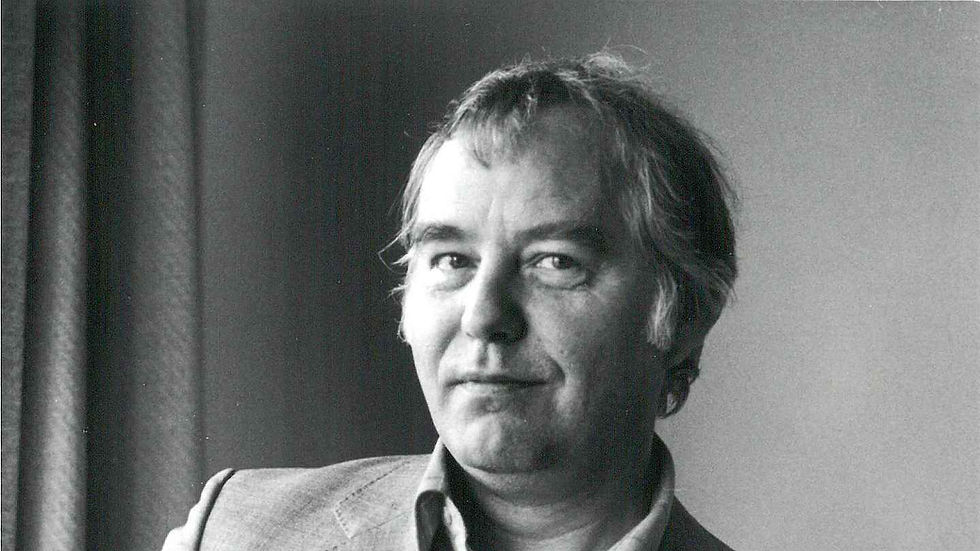

- Árni Heimir

- Sep 30, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2023

Iceland has a remarkably brief tradition of “classical” music—in fact, it is still less than a century since the first symphonic performances were given there, by the touring Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra in 1926. Opera took even longer to manifest itself, and the first full-length Icelandic opera was composed as late as 1974: Jón Ásgeirsson’s Þrymskviða (Thrym’s Poem), based on a story from the medieval Poetic Edda.

Yet there was another opera in the making, 30 years before, that never saw the light of day. Jórunn Viðar, Iceland’s first woman composer, studied at the Berlin Conservatory from 1937–39 but was forced to return home when the outbreak of World War II was imminent. After a few years of private composition lessons in Reykjavík, an opportunity to further develop her talents came unexpectedly, when her husband was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer and was flown—in an unheated military plane—to the United States for immediate treatment. Fortunately, he survived, and Viðar joined him in New York in 1943, where they lived for two years before returning to Iceland. During her stay, Viðar studied composition with Vittorio Giannini at the Juilliard School of Music, and one of her projects there was a particularly ambitious one: an opera called King Snow, or Snær konungur in Icelandic. The librettist was her younger sister Drífa, who, as it happened, was also in New York, studying art with the French Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant. The two had already collaborated on smaller projects for a children’s program on Icelandic Radio a few years earlier, including a musical setting, sadly lost, of Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

Their new project was loosely based on a character from ancient Nordic romances, King Snow, who has daughters called Mjöll, Drífa, and Fönn (all of which, not coincidentally, are some of the many words for snow in the Icelandic language). Jórunn and Drífa Viðar created their own libretto in which the ill-natured, misanthropic Snow—something of a Nordic Grinch, if you will—is challenged when one of his daughters wants to marry Fjalar, who has been raised by dwarves. Snow is furious, since he wants to marry his daughter off to the evil Kolur instead. The dwarves launch an attack on Snow, aided by Eldgríma (the name literally means “Fire-Mask”), a fairy spirit who controls the fire looming within the mountain where Snow resides.

King Snow, therefore, has some of the classic traits of an operatic libretto: a love triangle, including a soprano and tenor obviously meant for each other, and an antagonist providing the plot’s external conflict. Not quite as typically, its cast of characters includes dwarves and fairies, and the final scene includes a volcanic eruption, when Eldgríma unleashes all her forces to destroy Snow with fire, but to no avail. In the end, the dwarves must concede defeat, although what happens to the two lovers is unclear from the extant drafts.

What survives of King Snow are 82 pages in piano score and an additional 34 pages containing two fully orchestrated scenes. The latter were presumably done under Giannini’s tutelage, since Viðar in her letters refers to working on the orchestration with her teacher. She seems to have composed music to most of Acts I and II, but the final act with its dramatic conclusion only survives in Drífa Viðar’s text draft. By December 1945, both sisters had returned to Reykjavík, but Drífa continued her studies in Paris soon afterwards, thus precluding further collaboration on the opera. What survives, however, is delightful. The surviving draft has been kept by Viðar’s daughters since her death in 2017, but last week they brought it to me and I have had the immense pleasure of playing through it several times. Like most of Viðar’s music, the score shows the influence of traditional Icelandic music, yet the harmonic colors and lightness of touch are fully her own.

Unfinished operas are a well-known phenomenon in music history. In some cases, particularly when completion was prevented by the composer’s death, others have taken on the (sometimes substantial) task of filling in whatever gaps remain—Puccini’s Turandot and Berg’s Lulu being the most celebrated examples. Other drafts were dropped for whatever reason and have never been staged; they remain curiosities, with perhaps a recording or two available for the truly devoted. Among these are Beethoven’s Vestas Feuer, Rachmaninoff’s Monna Vanna, and countless others. Jórunn and Drífa Viðar’s King Snow seems destined to remain in the second group, especially given that no music for the final act has survived. However, it would certainly be a worthwhile endeavor for a group of singers to perform a few of its scenes with piano accompaniment, bringing to life what could have been Iceland’s first opera—even though most of it was composed on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

Such a great discovery!! Thank you for sharing it! Takk fyrír!